Category Archives: Statehouse

Some terms have a technical meaning and a common meaning, and the common meaning has a “normative slant.” The technicians know how to use the terms in the technical sense. But sometimes the common meaning slips in, in such a way that using the term ends up making two arguments with one word.

If one isn’t careful, using such terms can lead to confusion. Who’s to blame is not always clear. It could be the technician who uses the term or it could be interlocutor who misinterprets or misidentifies the technical meaning.

I have a list of three terms here, in ascending order of how knowledgeable I am about the technical definitions.

THE TERMS.

Marginal.

Title(s) of technicians. Economist; political scientist.

Technical meaning. The extra amount one is willing to spend to get the next widget. Or, somewhat less technically but still bound up with what technicians mean: the amount of change a given policy will bring about in a given direction.

Common meaning. An amount that is unimportant or trivial.

Normative slant to the common meaning. Mostly neutral, but it can swing either way depending on whether “amount” in question is good or bad.

Possibilities for confusion. When people speak of changes “on the margins” or assert that such and such policy will bring about “marginal” changes, they may have in mind the technical meaning. But sometimes they let slip in or leave unaddressed the common meaning. If it’s a somewhat harmful, but in his/her opinion necessary thing technician is advocating, he/she leave themselves open to the charge that he/she is minimizing the harm.

Sometimes, too: The size of the margin–not whether a marginal change will be brought about–is really what is under dispute. Simply pointing out that change (for the better or worse) will occur along some margin does not 1) demonstrate how much the change will be and 2) whether the change is worth it.

Exploitation (Marxist version).

Title(s) of technician(s). Marxist theorist; activist.

Technical meaning. Expropriating the surplus value of a worker to pay the profits of the person to whom the worker sells his or her labor. (Other technicians may have other meaning, but I’m focusing on the Marxist version.)

Common meaning. Somehow compelling someone to do something that they don’t want to do and that harms them.

Normative slant to the common meaning. Bad.

Possibilities for confusion. One sometime activist I knew who was steeped in Marxist theory often used the word “exploitation” to great emotional effect when describing the treatment of workers and the need for a revolution. And yet if you bring up examples of workers being treated well or workers as a whole benefiting from the prevailing economic system, then that same Marxist will fall back on the more technical meaning of “exploitation” and explain what they really meant was that the workers’ surplus value, etc., etc.

Historical.

Title(s) of technician(s). Historian.

Technical meaning. Representing the phenomenon of change over time. I believe it can represent persistence over time as well. The key point is that change happens (or doesn’t) but it can be explained by people’s decisions or by contingent, unforeseen happenings. This is probably a modern conceit. Historians in earlier times sometimes appealed notions of “forces of history” or “cycles of history” or “spirits of history” (e.g., Zeitgeist, Volksgeist, Ortgeist). I’m not saying my definition is true for all times and places and people, just that it’s the prevailing definition among those who were trained professionally in history and abide by professional history’s norms.

Common meaning. True and factual story of what happened.

Normative slant to the common meaning. Good.

Possibilities for confusion.There are at least two ways we sometimes commingle the technical and common meanings. One is simply using the common meaning when it suits us and then relying on our status (such as it is) of “historian” to claim that it’s truth.

The second is to speak as if merely demonstrating that a given belief or position or attitude is “ahistorical” we have therefore invalidated it. This is wrong, or at least “confusing,” because it assumes that historicality is the only measure by which to judge things. It judges people by the standards of professional historians even if those people did not claim to be abiding by those standards in the first place.

CONCLUSION.

Apologies.

There’s a lot I don’t know about the above terms. I’m least confident with “marginal.” Not being an economist or trained in economics, I suspect I’ve got it wrong on some level. So please correct me.

I feel a little bit more confident about “exploitation” and Marxism. But to be clear I’ve never read Marx to any significant degree, and most of what I “know” comes from reading Marxist-inspired historians and talking with people like my sometime activist acquaintance. And perhaps the “confusion” I talk about is just an anecdatum from my activist acquaintance.

Even with “historical” I might be off despite my training. In my anecdotal observation and experience, historians aren’t usually trained in grad school to examine the assumptions of history. Instead, grad school socializes them into the norms of the profession, and among those norms are the assumptions I mention above. My experience is no exception: I’ve given these assumptions some thought, but haven’t really investigated them systematically.

Envoi.

My takeaway, though, stands. We should beware how we use technical terms. It’s not only that there’s room for confusion, there’s also room for deception or at least lazy argumentation. And while the blame can’t always rest with the technicians, it sometimes can.

If I am to pick one low-cost way for ruralia and other places with physician shortages, it would involve waiving residency requirements:

Dr. Faris Alomran, a British-educated vascular surgeon working in France, says, “My first choice after medical school was to practice in the U.S. In fact, for most [English-speaking] people, in terms of language options, they are somewhat limited to Australia, Canada, and the U.S.”

But he didn’t end up crossing the Atlantic. “In the U.S. I would have had to do five years of general surgery and a two-year fellowship in vascular surgery to be a vascular surgeon. Seven years total. I got an offer in Paris to do a five-year vascular surgery program. They also reduced my training by one year since I had done two years in the U.K.”

Juliana, a physician originally trained in Brazil and currently in an American residency program, agrees that migrating to the U.S. could have been easier, especially if redundant training were removed. “Repeating the residency is not an easy thing, and many times it’s very frustrating. I do not think the internship [that I’m in] will add much to my future career. Having trained in America for the last four months has helped me understand cultural differences [between the U.S. and Brazil], but it has also made me wish I were allowed to skip some steps.”

This article seems to focus on attracting the best and the brightest, though that’s less my primary concern. (It’s a heck of a secondary concern, though!)

There is a perception that doctors aren’t going to come here to work in Idaho, and that may be true for the best and brightest. But there are a lot of doctors who would be willing to come here for a paycheck (which, by international standards, are just fine in Idaho). A lot of them wouldn’t stay there, but some would even after released from a 5-10 year requirement. (Yes, even some non-European ones would.)

I’m not optimistic on this happening, though, because while many argue the requirements are self-enriching gatekeeping, in my experience even those places where the doctors are suffering from the shortage (by having to work insane hours, for instance), they are pretty resistant. It’s a matter of professional pride. If another country (besides Canada) aligned their medical training with ours, it would be possible. But… other countries aren’t anxious to bend over backwards to make it easier for their doctors to leave.

That said, people make the AMA the bogeyman for all things gatekeeping-related, but they’re actually open to it. As it happens, and as I will keep saying from now until the end of the time, they don’t weird very much power. The power belongs to the states, and the medical board within the states. The AMA may have some influence with them, but they are extraordinarily conservative and inflexible institutions as far as such things go. They recognize the problem, but don’t see it as their problem.

And from a more cynical standpoint, the looser the restrictions the less important they are. There is a reason that one particular state ran my wife through the ringer over (her own person) medical records that were destroyed in a hurricane, let the process drag on for over a year, and then demanded another application fee (of $1000) because the original one had lapsed. In a state where her skills and professional interests aligned perfectly with a state, and a shortage precisely where she would have gone.

Across the board, the credentialism is just crazy. My wife has delivered over 1,000 babies, and performed more than 300 c-sections, and she could still never be given privileges in county hospitals covering some 70% of the US population. Doctors just out of obstetrical residency, who have delivered far fewer babies, would have no problem at those same hospitals. It’s a long story as to why this is the case, but the long and short of it is that if she wanted privileges at these hospitals, she’d have to go back to residency for three years. All of her experience would only let her skip a single year.

It’s interesting how sometimes you have a political passing observation about something, consider it true but probably not that important, but that becomes incredibly important. Think of it like “Those tires are looking kind of thin” thirty minutes before they blow open on the Interstate. A few years ago I thought to myself, “You know, first past the post isn’t a good way to hold primary votes.” I was thinking more for things like senate races, but that actually became very important. In early 2015, I thought “I think people are overestimating the ease with which Jeb Bush will win the nomination. This might be the year the establishment loses” This struck me as potentially important, but I thought at the time it might mean that Scott Walker or, worst case, Ted Cruz. And here we are.

Perhaps the most important of these things was about immigration. After running some numbers, it became apparent that the “Campaign Autopsy” as it related to the Hispanic vote and Comprehensive Immigration Reform simply wasn’t true. There were a lot of things responsible for the GOP’s loss, but the Hispanic vote wasn’t really among them. They didn’t put that in there as an analysis of what the party needed to do in some irrefutable need, but what its leaders wanted to do. With that, it became obvious that even after the failure to pass anything in 2013, the party really was going to screw the immigration restrictionists as soon as it could. Since I am uncommitted on the issue, this realization made me neither elated nor angry. It was mostly just an observation. One that would become very important. (more…)

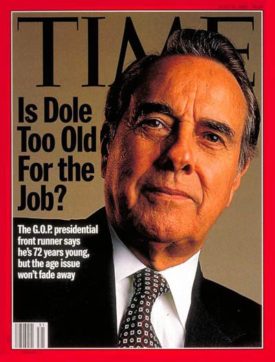

A lot of Republicans – including Rudy Giuliani – are trying to make an issue of Hillary Clinton’s health. With the exception of a photo here and there that looks less than flattering, this is mostly a product of her age. Some have argued sexism, but other than a general belief in sexism and female age, there’s just not much reason to believe that’s especially true. It’s not as though we haven’t been here before.

The media’s dismissal has lead to some accusations of media bias, because of Bob Dole above and John McCain in 2008. Hillary Clinton will be 69 before election day, Dole and McCain were 72. One could argue that 70 is the cut-off, but there’s no special reason it might be. More likely it’s that while there are allegations that Hillary Clinton has health problems, Dole and McCain both had actual infirmities going back to their war experience.

The media’s dismissal has lead to some accusations of media bias, because of Bob Dole above and John McCain in 2008. Hillary Clinton will be 69 before election day, Dole and McCain were 72. One could argue that 70 is the cut-off, but there’s no special reason it might be. More likely it’s that while there are allegations that Hillary Clinton has health problems, Dole and McCain both had actual infirmities going back to their war experience.

Now, surely, it seems cruddy to penalize those two men for serving their country. It’s not especially fair. But it is what it is. Bob Dole had to shake with his left hand, and John McCain can’t raise his arms and had skin cancer to boot. Sucks, but there you go. Also, both McCain and Dole were running against young Democrats, putting the age issue in play. It’s possible that if Rubio or maybe even Cruz (though he looks older than his years) had won the Republican nomination, we’d be having a different conversation. Or maybe not. (more…)

The minimum wage in Seattle has gone up, but the sky has not fallen:

Pay for low-wage workers climbed more in real Seattle than in synthetic Seattle, while their employment rate and hours climbed slightly less.

“Seattle’s experience shows that the city’s low-wage workers did relatively well after the minimum wage increased, but largely because of the strong regional economy,” it says. “Although the minimum wage clearly increased wages for this group, offsetting effects on low-wage worker hours and employment muted the impact on labor earnings.”

Real Seattle had more businesses open after the law passed, while synthetic Seattle had fewer businesses close.

“We do not find compelling evidence that the minimum wage has caused significant increases in business failure rates,” the report says.

Boom!

The results are actually something of a rorschach test, though. The author starts off with the angle that, basically, employment in Seattle is growing like gangbusters and we don’t know whether or not the minimum wage is to thank for that. Which tells you a lot about where he’s coming from on the issue. The Washington Post takes a more sober view:

Things seem to be going pretty well since Seattle bumped the hourly minimum wage for large businesses up to $11 last year, from the statewide minimum of $9.47 an hour. Low-wage workers are getting more time on the job and making more money. Fewer businesses are closing, and more new ones are opening. The technology and construction sectors are booming. Even the weather cooperated for a change. The spring was unusually dry in Seattle, which was good for the city’s fishing fleet.

Yet the actual benefits to workers might have been minimal, according to a group of economists whom the city commissioned to study the minimum wage and who presented their initial findings last week.

The average hourly wage for workers affected by the increase jumped from $9.96 to $11.14, but wages likely would have increased some anyway due to Seattle’s overall economy. Meanwhile, although workers were earning more, fewer of them had a job than would have without an increase. Those who did work had fewer hours than they would have without the wage hike.

Accounting for these factors, the average increase in total earnings due to the minimum wage was small, the researchers concluded. Using their preferred method, they calculated that workers’ earnings increased by $5.54 a week on average because of the minimum wage. Using other methods, the researchers found that the minimum wage hike actually caused total weekly earnings to drop — by as much as $5.22 a week.

Minimum wage critic Adam Ozimek also throws his two cents:

The detailed approach taken by the study and the importance of unrelated economic trends highlight the care and precision that must be taken in studying the impact of minimum wages. For example, government administrative data were used, which allowed the same workers to be tracked over time, and ZIP codes were aggregated to create a comparison group.

The research also highlights the difficulty in simply looking at Seattle before and after the minimum wage hike to determine the effects. Seattle’s economy was growing strong before the hike, and as a result, the economists estimated that only 25% of the earnings gains that low-wage workers experienced by late 2015 can be attributed to the minimum wage hike, while the rest is due to a strong economy. Simply showing that Seattle added jobs after the minimum wage hike does not disprove job losses.

Another important takeaway is that this is not yet a test of what a big minimum wage hike does to a city. By the end of this study, Seattle had lifted the minimum wage from $9.47 to $11, which increased low-wage workers’ pay by 7.3% on average. Seattle is still far from the $15 minimum wage it will reach in January 2017.

Finally, the study shows the importance of tracking workers over time. By following low-wage workers who were employed in Seattle to begin with, the economists found that some adjusted to the hike by finding work outside the city. This suggests that even if total employment in an area is not affected by a minimum wage hike, low-skilled workers might be worse off as they are displaced by high-skilled workers and pushed out of the city.

Photo by Hikosaemon

Having said that, I actually find the results here somewhat alarming. If I am thinking of an ideal situation for a city to be able to absorb the impact of a raised minimum wage, Seattle going from just shy of $10/hr to $11/hr is a pretty good one. That there is a measurable effect there makes me wonder what’s going to happen when their minimum wage continues to climb. And what’s going to happen in California, where lower wages are both easier to justify and a competitive advantage in Bakersfield for precisely the aforementioned Spokane jobs.

It’s uncharted territory, and I’m glad I’m not the guinea pig.

Some rapid thoughts on very interesting @samtanenhaus in NYT mag, “How Trump Can Save the GOP” https://t.co/GuDyrrcSVy …

— David Frum (@davidfrum) July 9, 2016

1) In longest perspective, Trump’s role in US politics may be compared to that of William Jennings Bryan in 1896

— David Frum (@davidfrum) July 9, 2016

2) Bryan, like Trump, won a presidential nomination as tribune for a once dominant, now fading, group: small farmers; white working class

— David Frum (@davidfrum) July 9, 2016

I’ve been pretty upfront that I believe the American Revolution was unjust. Not 100% unjust. I concede some very good things that might not have happened, did happen or happened more quickly because of the Revolution. I also don’t claim that but for the Revolution, we would be right now sipping Molson’s and complaining about wait times and doctor shortages imposed by our single-payer system but being grateful that it’s not as bad as the National Health Service. But I believe the war was unjust enough that if I were around back then and had the same sensibilities as today and had the courage of my convictions, I would have opposed it.

That’s not a particularly brave or shocking thing to say in 2016. I don’t fear tar and feathering, which was by the way a really, really horrific practice and not the comical thing it used to sound like to me. I’m not going to lose my property be and forced into exile or shunned.

But my position takes some people aback, even my liberal and leftist friends. Some of my very liberal friends who in other contexts threaten to move to Canada get offended when I say the war was unjust. #notallleftistsorliberals , of course. I know a Trotskyist whose take on the Revolution is probably “something something bourgeois elites something something.” And there’s always the Howardzinnians, but even they claim the Revolution itself was just but that it was counter-revolutioned. (Actually, I’ve never read Zinn, so I don’t know exactly what he argues.)

Why bother harping on this? Even if you concede that the Revolution was an unjust war, there are other unjust wars the US has engaged in, usually wars more unjust, and certainly more recently, than that unfortunate escapade. And the Revolutionary War was a really long time ago. The scars have been healed. If celebrating it brings some people comfort, then why be “that guy” who gripes about it? If the founding document that allegedly justifies that war inspires or at least provides ideological cover for causes I support, then why diss it?

One reason why I bother: It’s the founding moment of the story we tell ourselves as a nation. There’s a holiday dedicated to celebrating it. I like my days off as much as anyone, and I feel fortunate to have a job that gives me July 4 as a paid holiday. But I’m not too keen on celebrating the type of political activism that gang of criminals in Boston engaged in and that gang of more polite apologists in Philadelphia “ennobled” with their declaration.

However, I can’t hide that I get a certain contrarian thrill from saying I oppose the Revolution. I agree with Kevin Vallier when he warns against the “contrarian trap.” I think contrarianism, as contrarianism, is a bad thing.

I end on “however, maybe I’m being merely contrarian” and not on “I think I’m right” because I don’t know whether I’m being contrarian or not and it’s best not to think too highly of oneself. But I do believe that war was unjust and we shouldn’t celebrate it.

Back in high school, I knew a kid named Merrick. He was geeky to an extreme, awkward. Not bad looking, but in his junior year in high school he got his first girlfriend with a girl who (also not bad looking) had not yet had a boyfriend. He left the state for college, and we lost touch. We ran into each other in a very chance encounter, and he had transformed into someone completely different. Gone was the awkward arrogance of the geek, in was the confidence of someone who had made it in the financial world of London with a gorgeous wife and a polished demeanor.

Merrick had some sharp words about the Brexit. He voted against it for largely cultural reasons, though he said it would be economically disastrous as well. There is not much unusual in his analysis except for the personal aspect. This is not what he wanted, but it’s not the end of the world for him. He has skills and education. He is not rooted in Britain and if they hang out an unwelcome sign, he can do his thing in New York or Dublin or anywhere else. If Britain decides it doesn’t want him, he has no need of it.

His readiness and willingness is a perfectly fair response. And it’s fortunate that he has the opportunity to pick up and go. There’s a decent chance I would, too.

There are two ways of looking at it.

I look at it as (potentially) London’s loss and Britain’s. Merrick and his ilk are law-abiding, educated money-generators. Any sane country should want as many of them as possible. If he leaves London I hope it’s to return to the states. I want as many Merricks as we can find, regardless of their country of origin. I’m not in favor of open borders, but there aren’t that many of his caliber and if we took them all in, it would be almost all upside. Okay, okay, when it comes to Merrick I may be a bit biased, but you get the idea. I look at Merrick and people like him as a gain for any economy and culture that would have them, and I would similarly view their departure as a loss.

That’s not the only way of looking at it, however. Now, most uncharitably the other way of looking at it is looking at Merrick and noticing that he’s not white. He’s not not-white, either, exactly. He has olive skin, black hair, and a Scottish name. I suspect that as far as the census bureau is concerned, he’s white, but if a climate of hate were to take over Britain, he could very well be a target. In any event, no matter how good his accent, one thing he isn’t is English. He is as American as American can be, and most importantly he is a foreigner. Though he isn’t Jewish and doesn’t use the latter word, he’s a rootless cosmopolitan. Living in London.

All of these things are potentially important. In 2013, Alex Massie wrote a foreshadowing piece on the relationship between London and England, and it is pretty fraught. The internationalization and wealth of London has separated it from the rest of the country in a way that isn’t healthy. There was a predictable urban/rural divide, but notably England’s second largest city voted to leave. And despite Britain being an urban country, Leave won more votes.

The rest of the country doesn’t feel like it’s in it with London, and the response after the vote actually sort of confirmed that fact. “You want to leave the EU? Fine! We’ll leave you!” and something about inquiring whether apples were enjoyable. From afar, it looked a fair bit like the Remain’s motto could be boiled down to “London is who we are.” This sold better in London than outside of London. Which was lost due to the fact that everyone involved seemed to be from London.

As, of course, is Merrick. Which makes Merrick emblematic of three causes of resentment: He’s an immigrant, he’s based in London, and he’s in the money, both making good money and involved in the financial sector. As such, it’s really quite possible that the rest of England might not miss him as much as they should.

The debate that has erupted elsewhere is whether or not the Leave campaign was racist. Some observers are looking at other explanations, such as much of the above about London and inequality and the like. Others just don’t understand why we can’t call racism racism. It’s racist. It’s racist. It’s racist.

Which much of it is. Maybe most of it or maybe just some. It depends on how we define the term. But somewhere north of 0% of it is racism, and somewhere south of 100% of it is racism. Advocates of Leave like to argue it’s not racism because racism is unseemly and they themselves are not racist so what gives? Organizers, though, know that they have the racist vote and have done little to dissuade the votes that they need. Advocates of Remain, however, like the theory because it means that they can ignore the other side. If it’s racism it’s wrong. QED. But what do you do when you define something as racist, and 52% of the country is on the wrong side of that line that you drew? Saying racist isn’t enough. Even if we grant your moral and intellectual superiority, what do you do with a morally inferior electorate?

We often view these things as “local” problems. In the US, people are talking about what the GOP did to invite Trump, and of course Trump himself for what he is and isn’t doing. In Britain folks are blaming the Leavers and Cameron for giving the public a say. But there is something in the water, because it’s happening “locally” in a lot of places all at once. No matter how much Matthew Yglesias argues that Obama’s approval numbers suggest it’s a narrow phenomenon, 43% of the Democrats voted for a self-described socialist, 45% of Republicans voted for a megalomaniacal buffoon under a white ethnocentric banner, Labour voters remain firmly behind Jeremy Corbyn, the National Front is ascendant, AfD is ascendant, both the Golden Dawn and the Greek leftists are ascendant, and the mainstream parties in Austria combined for 23% of the vote in the last presidential election, leaving a runoff between the Greens and the far-right Freedom Party.

The consensus is breaking down. The historical tactic of dismissing the fringe as the fringe isn’t working anymore. Cosmopolis vs Hinterlandia has become an international phenomenon, and the fringe is closing in.

Merrick doesn’t need Britain. Britain, it increasingly believes, doesn’t need Merrick.

History of Europe:

War

War

War

War

War

War

War

Arguments about bananas.To be honest, I'll probably go with banana arguments. #remain

— Pavilion Opinions (@pavilionopinion) April 29, 2016